CANCÚN, Mexico—Emily Hamby of Rantoul, IL, was already a mother of two with gestational diabetes and placenta previa when she learned about her fetus’s diagnosis of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) while expecting her third child.

“I went to the doctor for regular blood work, and she said I had tested positive for something called anti-Kell,” recalled Hamby, 42. “I asked what that was. She’s a family care practitioner and told me that in seven years, she had never seen a patient test positive for anti-Kell.”

As Hamby soon discovered, hers is among the less common forms of HDFN, itself a rare condition that affects only about three to 80 of 100,000 pregnancies a year.

“Kell antibiodies are one of the worst types to get,” she said. “These antibodies can suppress bone marrow, causing the rapid destruction of fetal red blood cells and severe HDFN before or after birth. If you already have these in your system and your baby tests positive for the matching antigen, that baby is at risk.”

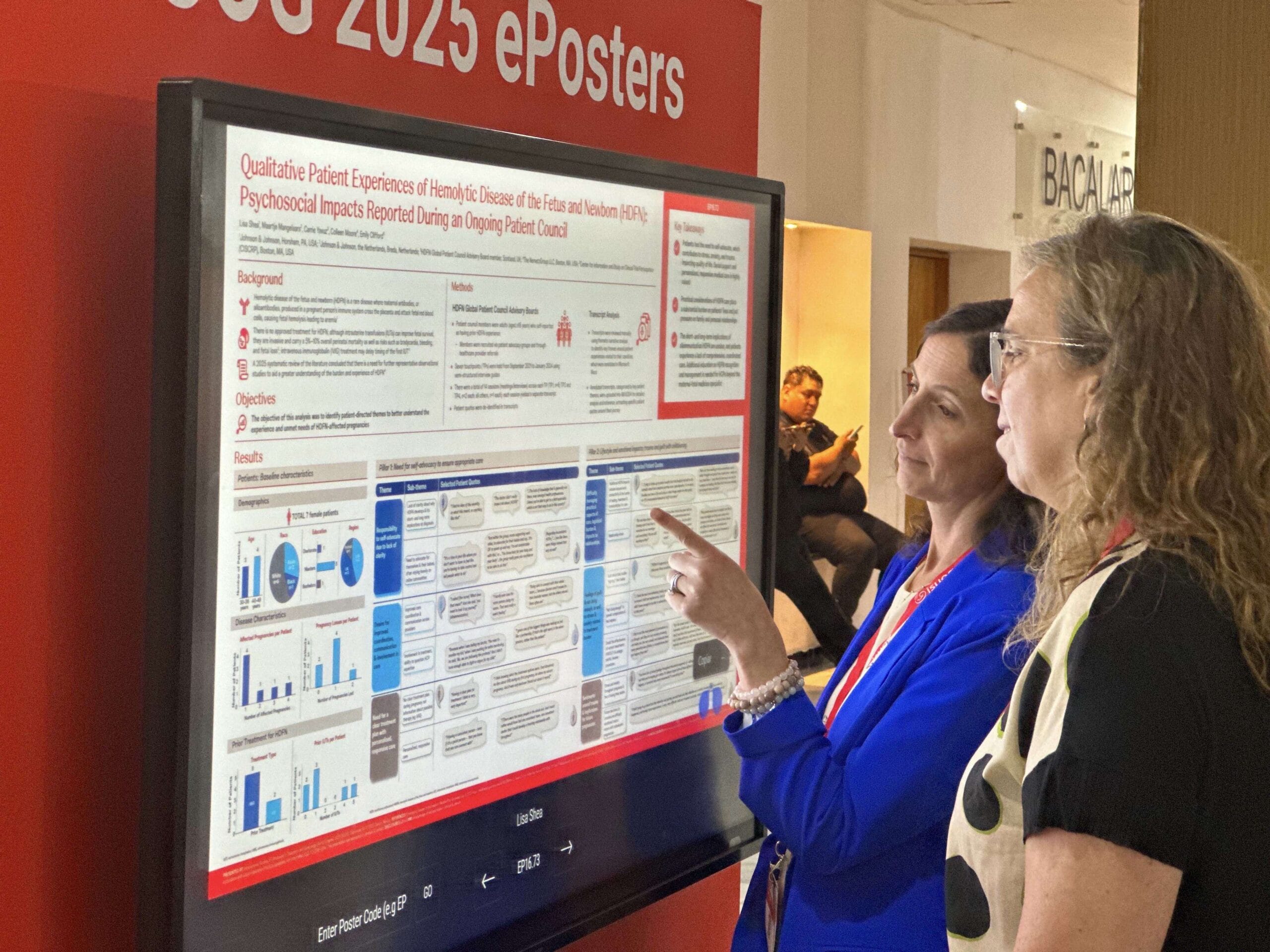

Registered dietician Lisa Shea is the director of global patient advocacy and engagement for immunology at Johnson & Johnson.

At the recent ISUOG 2025 conference in Cancún, Mexico, organized by the International Society of Ultrasound and Obstetrics and Gynecology, she presented real-world research on both HDFN and fetal neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT).

Self-advocacy in HDFN exacerbates patient burden

“We conducted qualitative research with global patient councils in both HDFN and FNAIT,” Shea said. “What we found was that for HDFN specifically, individuals feel the need to self‑advocate, which contributes to stress, anxiety and trauma, impacting their quality of life. Also, the practical considerations of managing an at‑risk pregnancy for HDFN place a substantial burden on a patient’s life, including pressure on the family and personal relationships.”

Likewise, she said, women with FNAIT “felt that the current treatment protocol is burdensome, and there’s a perceived lack of knowledge in the medical community, which can contribute to fear, confusion and uncertainty during pregnancy. This mental health impact is very large on both disease areas.”

Taylor Jeans of Marshall, Texas, knows this all too well. Jeans, 28, said her problems began with her first pregnancy, when she lost a son at only 25 weeks’ gestation for unknown reasons.

“During my second pregnancy, I was probably about 11 weeks along and started bleeding a little. I went to the ER, obviously with trauma from my previous pregnancy. They told me I was having a miscarriage and to go home,” she said, adding that she learned only later that she has the C and D antigens. “Being from rural east Texas, I didn’t even know what HDFN was.”

As it turned out, her son, Sauer, was born jaundiced, but a week of phototherapy cured him, and today he’s a healthy 3-year-old. Soon after, she said, Jeans became pregnant again. But this time, she and her husband Hunter “kept the pregnancy quiet because we had experienced loss before.”

Benelli, the baby girl Jeans was carrying, became anemic at 24 weeks and required three intrauterine transfusions (IUTs) at a specialized clinic in Houston. She was delivered via C-section at 35 weeks and spent two weeks in a neonatal intensive-care unit. After birth, she needed 3 more blood transfusions. Benelli is now 2 years old, said Jeans, and “completely fine.”

Shea explained that in HDFN, maternal alloantibodies cross the placenta during pregnancy and attack fetal red blood cells causing fetal anemia.

“This can affect infants by neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and persistent anemia, which then requires transfusions,” she said. “Currently, for HDFN, there are no nonsurgical interventions approved for pregnancies at risk for severe HDFN in the US, highlighting the significant unmet needs for new safe therapies.”

According to Shea, the severity of HDFN often increases with each subsequent pregnancy.

“The mental health impact and burden on these patients is really important when thinking about how to manage this disease. The need for education in the medical community is also important,” she said. “Obstetricians in general are the ones that may identify an at‑risk pregnancy. What we found in speaking with patients is that while overall, maternal‑fetal specialist medicine practitioners were knowledgeable, there was definitely gaps in other types of providers during pregnancy.”

Hope on the horizon for HDFN-affected families

Johnson & Johnson is conducting testing for nipocalimab, an investigational FcRn blocker designed to substantially reduce IgG—including harmful IgG autoantibodies—without additional detectable effects on other immune functions. Nipocalimab is believed to do this by blocking the placental transfer of maternal alloantibodies during pregnancy.

In June 2023, J&J announced phase 2 data from its proof-of-concept, open‑label UNITY trial of nipocalimab to treat pregnant women at risk for early‑onset severe HDFN. Full results were published in August 2024 in The New England Journal of Medicine. The trial showed that the drug delayed or prevented severe fetal anemia requiring intrauterine transfusions (IUTs) and that 54% of participants met the primary endpoint of a live birth at or after 32 weeks without needing an IUT.

J&J subsequently initiated a phase 3, placebo-controlled randomized trial known as AZALEA to study the efficacy and safety of nipocalimab in that same patient population. AZALEA is being conducted at 62 sites in 20 countries around the world.

Hamby, the HDFN patient from Illinois, was diagnosed with Kell antibodies at 10 weeks and started getting weekly scans at 18 weeks. Those scans were all normal until week 27, at which her Multiples of the Median (MoM) was approaching 1.5.

“We did the scan the next morning and it was normal. So we arranged a telemedicine consulting session with a Kell-related HDFN specialist in Ohio, and the decision to deliver was made. My daughter Vada was born at 33 weeks and 4 days, weighing 5 lbs, 4 oz.She went straight to the NICU.”

Vada is now 3 years old and is negative for the Kell antigen, Hamby said.

“We were concerned she might develop it,” she said. “My first child, Miles, who’s now 16, was very sick at birth, and we didn’t know anything about Kell antibodies. He was quite jaundiced for a while.”

Concerning nipocalimab’s potential, Hamby said she thinks the drug is “wonderful.”

“It’s groundbreaking, especially for moms who have anti-D, anti-Kell or anti-c, since those are the 3 most aggressive types,” she said. “If this new medication can really prevent hemolytic anemia, that would be quite amazing.”